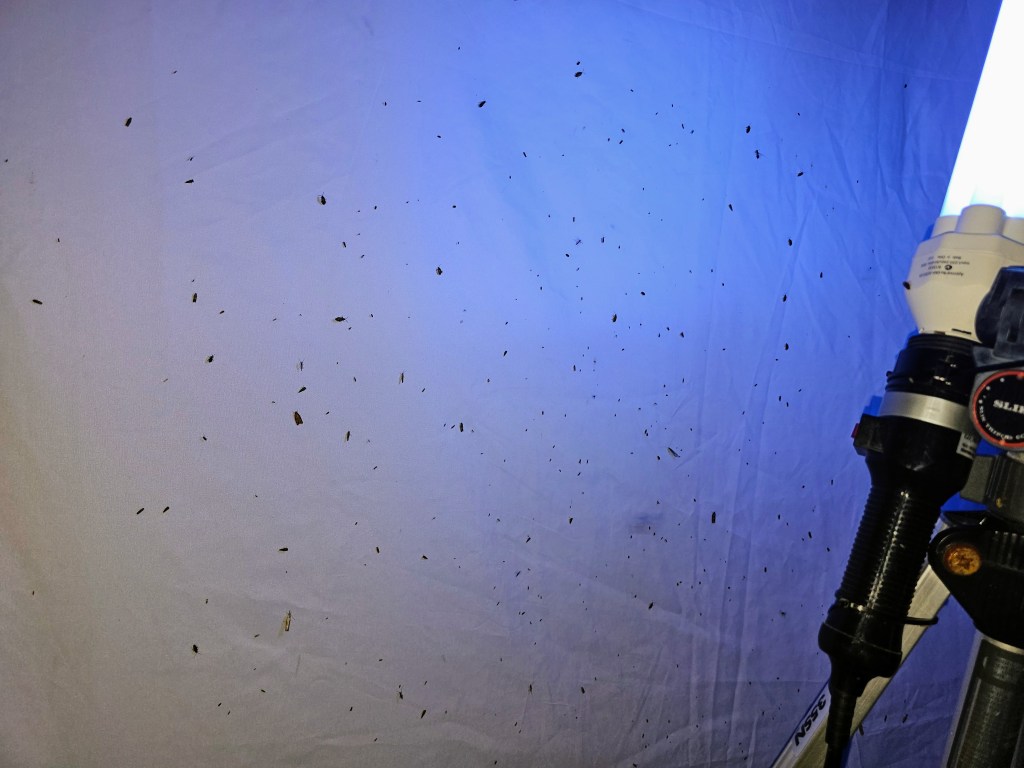

This was only my third attempt at running the UV light at my new property, but this was the first night that was really ideal. Warm, humid, and calm. Exactly what was needed for all the tiny critters to rest on the sheet and await being photographed.

Over the years of recording at my previous property (only a few km away from this one, but deeper in suburbia with less natural spaces around) I’d recorded 515 species attracted by the UV light. I’m expecting similar at this location, although likely a different set of species. Previously reviewing the species observed at a UV light at two separate locations in greater Adelaide, both in suburbia but one much closer to the Adelaide hills, I’d found that almost 50% of the species seen were at one or the other property. I’d expected most species would be present at both, but this wasn’t the case. I’m really hoping that applies to my new property and I’ll encounter many new species.

I’ve changed my setup somewhat at this new location. Rather than mounting the sheet and light on the side of a shed or at the entrance to the patio, I’m able to mount it on an Australian classic, a Hills Hoist. It’s surprisingly ideal. I can set the height and direction as needed, and it’s much quicker to set up. I’m still using a 50W UV globe and a handheld work light fitting with extension cord attached to a tripod.

This night I only ran the light for around 3 hours past sunset, as I typically do. I happen to have a park with large Eucalypts next to my property, so I’ve been setting the sheet up to face that direction, and it is showing in the species I seem to be attracting. On this night I recorded 30 species. A few highlights shown below.

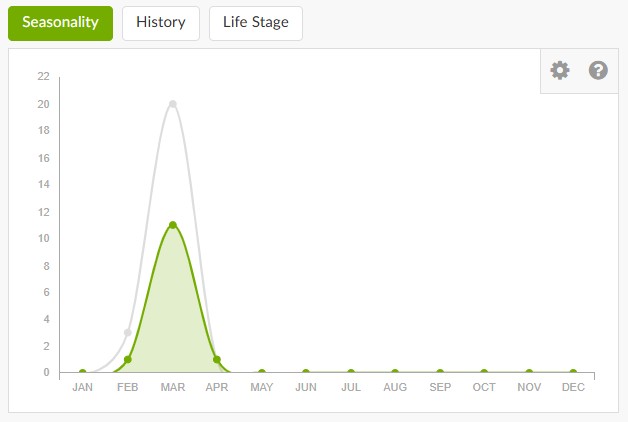

Syringoseca rhodoxantha, a Concealer Moth in the Family Oecophoridae, a stunning red-brown with cream spots, the larvae of which are thought to feed on Eucalyptus. I recorded this 6 times on my previous property in 2020, 2021, and 2022, each time between March 7th and March 19th. It’s not surprising that the adult Moths emerge at roughly the same time each year, but I’m often amazed at how narrow the time period is, often spanning only a couple of weeks. After which I say goodbye to seeing the species for a whole year.

Other than the original 1888 species description(1) and a comment found elsewhere that they are thought to feed on Eucalypts, here is all the information I could find on this species: What does the larva look like? Unknown. What does it eat? Unknown. How does it pupate, where, and for how long? Unknown. Where are the eggs laid and what do they look like? Unknown. How long do the moths live? Unknown. Hmm….so your guess is as good as mine as to how we might support this species in our local environment.

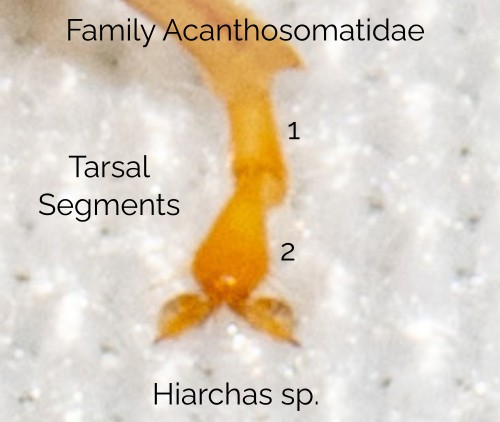

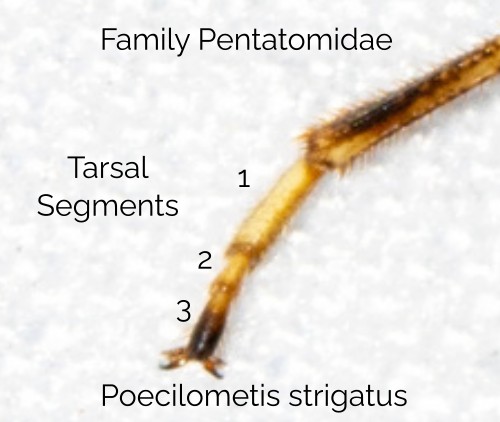

It’s not uncommon that I find a species from the Superfamily Pentatomoidea attracted to the UV light, often a Stink Bug and usually a Brown Shield Bug (Poecilometis strigatus). But this night I was lucky enough to find a Shield Bug. These are in the same Superfamily, but are from the Family Acanthosomatidae. I’ve only ever recorded 3 Shield Bugs. One from Scott Creek Conservation Park, one from Oaklands Wetlands, and now this one. The particular individual I encountered appears to be a nymph of a species in the Genus Hiarchas. I don’t know enough about this group to say whether it can be IDed any further or whether it is impossible to be refined to species from a nymph.

This find presented an opportunity for me to pull out my copy of Plant-feeding and other bugs (Hemiptera) of South Australia : Heteroptera, (Gross, Gordon F.; 1975-76). I was able to utilise it to find that Shield Bugs in the Family Acanthosomatidae can be identified (in most cases) by their feet having only two tarsal segments, whereas other Families in this Superfamily such as Pentatomidae have three tarsal segments. Unfortunately the key notes that Acanthosomatidae are not covered in the book, so I wasn’t able to refine it further. Based on other reading(2)(3) I’d do well to collect the specimen next time and photograph the underside as the ventral characters are important to separating out the subfamilies.

What can I find out about this Genus? Not much. Acanthosomatidae are typically herbivores. Not much more I can determine. Likely an arboreal, diurnal, sap-feeder. I’ll keep an eye out for an adult specimen.

Check out the arms on this one! This little critter, doing its best to pretend to be a Praying Mantis (at least in our eyes), is in fact in the Order Neuroptera with the Lacewings and Antlions. This is one of the Mantidflies (Family Mantispidae). In a case of convergent evolution, they’ve developed raptorial forelimbs similar in design to that of the Praying Mantises.

It wouldn’t be surprising if you’ve never seen one before as these are roughly 10 – 15mm long and very svelte. I’ve only ever encountered the adults when they visit the moth sheet, and have never seen the larvae.

This particular Genus is endemic to Australia. The subfamily in which they reside, Mantispinae, have an amazing lifecycle. The first-instar campodeiform larvae are mobile and seek out either female Spiders or Spider eggs. If they encounter a female Spider they’ll climb aboard and remain there until the Spider produces an egg sac at which point they’ll demount and enter the sac. In the interim they can feed on the spider hemolymph. (I haven’t a clue how the larvae would determine male from female Spiders). Once inside the egg sac they’ll feed on the eggs by draining the contents with their piercing/sucking tube, then pupate in the egg sac. The Genus Campion are known to prey on the eggs of Wolf Spiders and Tarantulas. Species within this Genus look quite similar and dissection is needed to identify to species level, so I think my iNaturalist records of these will remain refined only to Genus.

Here’s where having a camera that can take macro shots comes in handy. On nights like this the majority of species that visit the sheet are tiny. Depending on the season and location, you’ll get some larger Moths visiting, but you’ll still have an abundance of tiny critters. Many of which may not be much more than a dark smudge, at least to my aging eyes. But they still represent the majority of species and are a critical part of the local environment, and certainly worth recording and investigating. Below I’ve shown a couple of size comparisons that really go to show the variation in scale between species. The first is a Cricket along side a much smaller Ant-like Flower Beetle, and the second is an African Black Beetle (I think) along side a tiny unidentified Beetle.

In all I recorded 30 species this night, and if I’d had more time could have easily recorded more. All of these records are uploaded to iNaturalist and appear in the ‘Melta Way Biodiversity Park‘ project, in which I am developing a species list for a local suburban park. A selection of additional photos from the night are shown below.

(1) Linnean Society of New South Wales. & Linnean Society of New South Wales. (1875). Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales (Vol. 2, p. 933). Linnean Society of New South Wales. Link.

(2) Daley, A. & Ellingsen, K., 2021. Field Guide to the Insects of Tasmania (12.03.2025). Link.

(3) Kumar, R. (1974). A revision of world Acanthosomatidae (Heteroptera : Pentatomidae): Keys to and descriptions of subfamilies, tribes and genera, with designation of types. Australian Journal of Zoology Supplementary Series, 22, 1-60.